I was born in

Quito, Ecuador to a

Taiwanese father

and a Korean mother.

Words & Photos provided by Sandra

It was difficult being the one who stood out in a country where there isn’t much diversity. I was exposed to racism and prejudice from a young age.

I often heard racial slurs directed at me and my family even just walking down the street. I remember the name-calling quite vividly even now. At school, some kids would make fun of my eyes and call me names. I knew I was different from a young age.

My older sister was my role model. She taught me to not be ashamed of who I am. I believe I could grow up with more confidence because of seeing how she handled bullies and how she was unapologetically herself. I know that my upbringing impacted how I am as a person now, especially in my struggles with social anxiety.

But even through all that, I never rejected my culture or race.

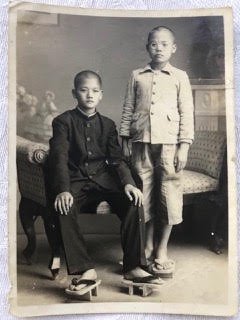

My father grew up in a small island off mainland Taiwan to a family of fishermen and farmers. He was to inherit my grandfather’s fishing boat, but persistent seasickness led him to move to the mainland where he started work at a very young age. In his late 20s, he emigrated to Ecuador for job opportunities.

My maternal grandfather was a traveling architectural engineer. He fell in love with Ecuador after briefly working there and decided to move there from Seoul, which is how my mother ended up in Quito in her teens. A mutual friend introduced my father to my mother, and they married a few years later.

Growing up, my household included my parents, sisters, maternal grandparents, and Korean uncle. I am not fluent in Korean, but I grew up hearing it.

My paternal grandparents never left Taiwan. I only met my Taiwanese grandfather a few times when I was young before he passed away. I sometimes wonder what it would have been like growing up with them.

My Korean grandmother cooked every single thing from scratch. When she made kimchi, it would take her days and there would be buckets full of fermented ingredients.

My dad wasn’t a good cook, but we had family friends who were, and they indirectly helped me learn more about my Taiwanese heritage through their cooking, as well. I learned to love the flavors of my cultures in this way.

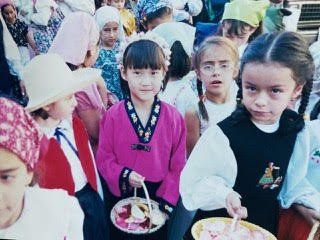

Every Saturday, my sisters and I went to Korean language school in the morning and Mandarin Chinese classes in the afternoon. Although I disliked those lessons then, now as an adult I can appreciate how significant this intensive language learning was for understanding my heritage.

My parents spoke to each other in Spanish, since neither of them are fluent in each other’s mother tongues. My dad strictly enforced my sisters and I to speak to him only in Mandarin and that we speak Korean to my mom.

However, my mom felt more comfortable speaking to us in Spanish because she moved to Ecuador when she was a teen. This is probably why I learned Chinese better than Korean, but I don’t resent her for that.

At home, the cultural dynamics were familiar, but in school I stood out like a sore thumb. My sisters and I were the only Asian students for most of our childhood. Though I found solace at my weekend language schools, I still felt like there was an invisible separation; like I lived in between cultures. In Chinese school I wasn’t fully seen as Taiwanese, and in Korean school I never felt fully Korean.

Growing up in a multicultural household can be confusing at times, but I think it has made me more open-minded and empathetic. I’m more patient and inquisitive when learning about other people.

I have found that many people are not used to meeting Asians who speak Spanish. The confusion on their faces is something I take a lot of delight in. I often describe myself to others as being of Asian descent, half Korean and half Taiwanese, but grew up in Latin America and the U.S.

I’ve had both positive and negative experiences from both sides. Although Taiwanese culture was generally more welcoming, I always felt like there was a sense of awe at me being half-Korean.

On the other hand, with my Korean side, people seemed to focus more on me being half something-not-Korean, which created a sense of alienation. I felt more like an outsider.

I am thankful to the friends I met in both communities during my childhood who accepted me as I was, regardless of my parentage. I am thankful for my sisters, who were my first community.

Sharing the same trauma, similar experiences, struggles, and joys helped shape who I am today. And as cliché as it sounds, I would not want to trade my life for another, since I feel like it has been an interesting one.